I have been gone for the past few months because I have gone down the open source contributing rabbit hole, but it has not been all fruitless.

Most of this work has been spent contributing to the Deno standard library. While I'd love to talk about every little contribution, one of them stands out to me as the most interesting. Not because it was the most technically complex (in the end it only amounted to ~20 lines of code), but because it pushed me to learn how to read RFC specifications.

This PR implemented node's url.domainToASCII and url.domainToUnicode into

the compatibility layer, but the journey to obtain those 20 lines of code was a

lot longer than you would imagine. My first foray into implementing these ended

pretty abruptly when I came to realize that it would requite a spec-compliant

punycode implementation. What is punycode? Good question.

According to Wikipedia:

Punycode is a representation of Unicode with the limited ASCII character subset used for Internet hostnames.

Thanks Wikipedia, that has clarified nothing at all. To translate that into human language, punycode is a standard protocol that can be used to take any arbitrary unicode string and convert it into valid ASCII.

For those who aren't aware, ASCII is a specification that maps the numbers 0-127 to a bunch of characters. There's so much history to talk about on that front, but if you want a quick recap I highly recommend this video explained by education Youtuber, Tom Scott.

Unicode, in comparison to ASCII's 128 characters*, has essentially every character that can be written on a computer. This includes things like diacritic characters (é, ü, î, etc), non-latin characters (你好), and even emoji (😀, 🎉, 😱).

Punycode therefore defines a standard to convert from any of these characters into standard ASCII by the following two steps:

While this may not sound very difficult, it's enough of the pain to not warrant an afternoon or two of work. What I didn't realize in my first attempt at this PR is there is already a punycode implementation in the standard library so when I discovered this, I decided to give it a second shot.

* Not technically 128 characters in a traditional sense. There are a not-insignificant amount of control characters.

** A lot more technically challenging than this, but this is the basic concept

At this point, I was dedicated to making these functions a reality. I pulled out the most relevant specification that I could find and started reading it. Imagine my shock going from the clean and complete documentation of Deno, to this nightmare of a document.

RFC authors, if you are reading this, please invest in a markdown editor + renderer (an RFC -> markdown converter is not an awful project if anyone wants to pick that up). With a document so full of technical terms you would hope that it was clearly annotated, but this is simply not the case and it instead forces you into a rabbit hole of different RFCs.

If you're interested in hearing a more articulate individual explain their

gripes with old RFCs, I highly recommend

this post by the infamous GreyCat.

I will continue to bring up how unclear and awfully written these specifications are as you follow me through this journey.

The spec defines a set of instructions to follow for converting to and from

unicode. These steps are identical except for the usage of ToASCII and

ToUnicode which will be defined later. They are as follows:

AllowUnassigned to trueUseSTD3ASCIIRules to true but only for that labelToASCII or ToUnicodeToASCII make sure to join the labels by "." and not any of

the other unicode separatorsThat seems... fun to write. From reading this, it sounds pretty clear to me that

we need to implement ToASCII and ToUnicode before we even get the chance to

see if this algorithm works as expected. To keep it simple, lets only look at

ToASCII:

0000000-1111111 in binary), do step 2, otherwise skip to step 3AllowUnassigned

boolean from earlier. If this fails, "return an error" (?)UseSTD3ASCIIRules is true do the following checks. If either one fails,

"return an error" (?)xn--, "return an error" (?) if

notxn-- to the startWith the amount of question marks in these steps, you can probably guess how vague the actual specification is around these things. For reference, "return an error" in practice usually means either returning an empty string or actually throwing an error to be caught by the application.

I decided to sit down and implement this for the greater good of the javascript

community. After sitting down and writing the ToASCII I realized that there

was another function already defined by the name of ToASCII. To my horror, I

discovered idna.js which was just Deno vendoring the quite popular

punycode.js library. After further investigation I realized that ToASCII

actually implemented the whole conversion algorithm even if it was awfully named

to clash with the specification.

My change happened to only be around twenty lines of code because it simply called the already existing function in the source code.

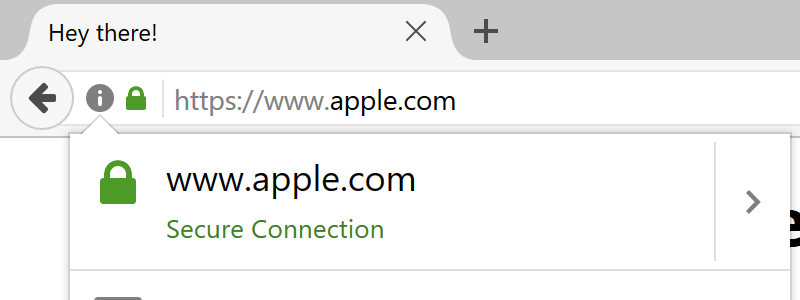

This RFC does actually have some modern relevance. In 2017, Xudong Zheng

published a blog post of a

proof-of-concept attack on https. In it, he demonstrates that you could buy the

domain xn–-pple-43d.com and browsers (at the time) would render it as unicode.

It just so happens that this domain name uses the Cyrillic "а" which looks

identical to the ASCII "a".

This kind of attack is only possible because of the limitations of human communication with symbols. If you're curious on what the result of this was, browser-makers pretty quickly patched out attacks like this by just showing the ASCII string if the characters in the URL looked like it mixed characters from similar character sets.

I hope that you have been able to take anything from this (admittedly humorous) journey that I went on. If you have any questions or concerns, don't hesitate to reach out to me! I'd love to have a conversation. I'm hoping to have a "year in review" post up by the 30th. See you then!

Comments